Power. I define it as the ability to make events and circumstances conform to one’s will. This, of course, presupposes the ability to compel or convince others to act in pursuit of that aim.

My interest in the subject of power sparked a desire to examine what some leading thinkers had to say about it. Their musings on power range from the instructive to the cautionary, and from the cynical to the utopian. Those concerned about the potential for abuse are perhaps the most numerous among the thinkers who wrote about power. (N.B.: This blog entry will focus primarily on power in politics or business, though much of what is written here would apply to other contexts as well, such as social and spiritual settings and educational institutions.)

Thinkers have much to say about the sources of power. Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus, by Mary Shelley, contains the following passage: “Beware; for I am fearless, and therefore powerful.” One might notice here some connection to Buddhist thought, which teaches that being without attachments is a path to strength. It makes sense that if one has no attachments, it frees them from fearing loss of them, and thus is a source of spiritual power.

Several commentators have focused on the qualities needed to acquire and maintain power. Some of these thinkers look to the role that self-discipline plays in this regard. Lao Tzu, the founder of Daoism, remarked that “Mastering others is strength. Mastering yourself is true power.” Tennyson wrote as follows: “Self-reverence, self-knowledge, self-control, These three alone lead life to sovereign power.”

Socrates went into more detail on this point, noting that true power comes through the control of one’s body and soul. He added further that power requires the discipline to act justly, live virtuously, and without need for anything. Also in this group of thinkers was the prophet Muhammad who wrote “The strong is not the one who is physically powerful, but indeed, the one who controls himself when angry.” Seneca, the great Stoic philosopher focused on the need for the powerful to withstand the hatred of others when he wrote: “To be able to endure odium is the first art to be learned by those who aspire to power.”

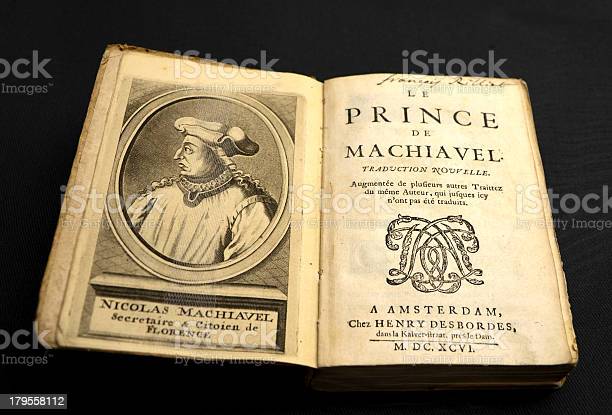

Of course, one of the most eminent thinkers on the acquisition and maintenance of power was Niccolò Machiavelli, whose thinking on power counsels one of the most amoral or even immoral approaches to the subject and whose most famous work, The Prince (published in 1513), is still studied today. (Indeed, the term “Machiavellian” has become synonymous with political theory that abjures morality.) Machiavelli took the view that power is everything in politics and that the acquisition of political power justifies any means for obtaining it. Contrary to the ethos of his time, he believed that goodness should always take a back seat to the acquisition and maintenance of power.

As for the style of leadership, Machiavelli, who took a dim view of human nature, considered that it is better for a leader to be feared than loved, because the former is more effective in ensuring obedience and therefore the preservation of the state. He felt that leaders should mask their intentions and act against anything, including mercy and religion, that threatens the state. At the same time, he recognized the importance of enjoying the devotion of those who are ruled by a potentate, when he wrote: “The best fortress which a prince can possess is the affection of his people.” After all, rule by terror or brute force can easily be a recipe for truncated rule — just ask Saddam Hussein, Muammar Gaddafi, and some of the other dictators out there who tried ruling that way, only to find their rule, and often their lives, cut short.

I turn now to what I would describe as a neo-Machiavellian work on power, the best-selling work, The 48 Laws of Power, written by Robert Greene and published in 1998. I will not mention all 48 laws (some of which are actually quite reasonable), but will focus on just a few examples of its cynical take on power. Law 2, for example, counsels the reader to be wary of friends, whom Greene considers prone to betrayal, envy, and being spoiled and tyrannical. Law 7 advises leaders to exploit the wisdom, knowledge, and effort of others, but to always take credit for the product. Law 14 advises readers to pose as a friend to others and to use spies to gain an advantage. Law 20 advises against making commitments to others and playing them off against each other, while Law 27 counsels leaders to play on people’s needs with a view to creating a cultlike following. Finally, Law 43 advises leaders to seduce others by playing on their emotions, beliefs, and fears. These are, of course, just a sample of Greene’s “laws,” but they give the reader a flavor of his thinking — an approach that abjures virtue, honesty, transparency, and other values many of us care about and instead encourages leaders to practice deceit, betrayal, subterfuge, and exploitation. To me, this is repugnant stuff.

As for what power consists of, Gandhi identified two types of power: that exercised by punishment and that exercised through love. Not surprisingly, he felt that the latter was more effective, asserting in his articulate manner that “The day the power of love overrules the love of power, the world will know peace.” Francis Bacon wrote the well-known aphorism “knowledge is power.” This makes sense, because knowledge enables us to do things we otherwise could not do and provides an opportunity to outsmart and outmaneuver opponents. (John F. Kennedy would later borrow Bacon’s phrase in one of his speeches.)

Turning to some cautionary thinking about the abuse of power, Albert Einstein stated that “The attempt to combine wisdom and power has only rarely been successful and then only for a short while.” The Founding Fathers were deeply concerned about the concentration and abuse of power, which led them to disperse power and provide for “checks and balances” in the Constitution of the new republic. They were particularly concerned about the emergence of demagogues and tyrants, a consideration that led them to provide for impeachment in that same document. George Washington was quite cynical, noting that “Few men have virtue to withstand the highest bidder.”

Other thinkers focus on who is attracted to power, but don’t have much positive to say about them. In this regard, the scientist and author David Brin, had the following to say: “It is said that power corrupts, but actually it is more true that power attracts the corruptible. The sane are usually attracted by other things than power.”

In Plato’s Republic, the philosopher had much to say about who should and should not be given power. Democracy, he noted, breeds leaders who lack proper skills and morals and who are likely to become demagogues. Instead, political power should flow to what Plato referred to as “Philosopher-Kings,” leaders specially trained to be wise, virtuous, and selfless and who live simply and communally. Plato believed these individuals would be best placed to understand what is truly good and just. In this regard, Plato also remarked that “Only those who do not seek power are qualified to hold it.” Of course, such a standard would leave the world with but a handful of leaders worthy of power.

As for the goals of power, Martin Luther King distinguished between power for power’s sake, to which he objected, wanting instead “power that is moral, that is right and that is good.” Compare this with the following chilling passage from George Orwell’s 1984:

“The party seeks power entirely for its own sake. We are not interested in the good of others; we are interested solely in power, pure power. . . . We know that no one ever seizes power with the intention of relinquishing it. Power is not a means; it is an end. . . . The object of power is power.”

Even though the above quotation is from a work of fiction, it is not very far removed from what actual tyrants believe and might even say.

Still other attributes of power have received attention from thinkers. John Tillotson, the 17th century cleric, focused on the tribulations of those who possess power as follows: “Those who are in highest places, and have to most power, have the least liberty because they are most observed.” And the author Alice Walker offers this lesson on how people lose power: “The most common way people give up power is by thinking they don’t have any.” In other words, what Walker is telling her audience is that they have more power than they think they do. In contrast to Socrates and Plato, the French philosopher Michel Foucault tried to separate power from philosophy. Margaret Thatcher, in amusing fashion, commented as follows on how you can tell that someone is not powerful: “Power is like being a lady … If you have to tell people you are, you aren’t.”

I offer one final note on power and that is that others (whether people or organizations) only have as much power over us as we are willing to grant them. After all, we remain free to defy power. Of course, one may have to pay a price for that defiance, perhaps even a heavy one, but the choice to obey is still ours. Perhaps no one illustrates this point better than the Russian activist Alexi Navalny. Putin would probably have been more than happy to let Navalny go into exile. However, knowing that he would almost certainly be imprisoned and possibly killed, Navalny returned to Russia and was promptly thrown into the gulag where he continued to harangue the Kremlin from behind bars until his dying day, which sadly came much too soon, undoubtedly at the hands of Putin’s henchmen..

I am sure it’s clear where my views fit in in all this. I do, of course, recognize that we must be careful about whom we grant power to and keep a watch on leaders lest they abuse it. Modern times offer many cautionary tales in this regard. But I do have faith in the ability of humanity to evolve ethically and morally in the way it acquires and uses power.

I sometimes perceive that cynics today view me and my optimistic thinking as akin to that of a dinosaur. Sometimes these individuals actually seem to enjoy the game, reveling in their “clever” manipulation of others to gain and exercise power. I am almost certain that such immorality predates the focus on ethical approaches to power. So, who exactly is the dinosaur, I ask?

Hello!

Good luck 🙂